Introduction

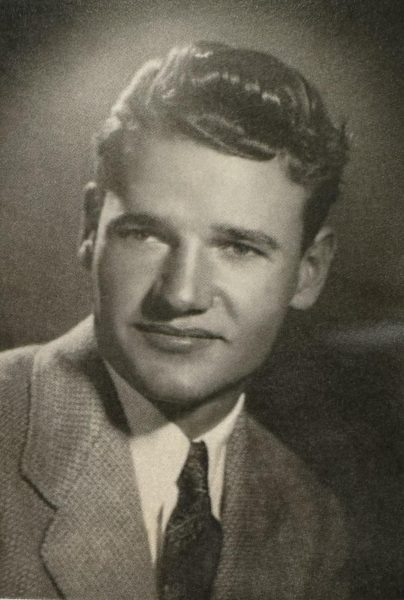

At 99 years old, Junior Bounous is not only a long-time neighbor of Timpview High School but also a cornerstone of its very existence. Before the school’s construction, Bounous owned the land that would become the school, and his generous donation made its creation possible. His story is one of resilience, adaptation, and quiet contributions that have shaped the community around him. He has many accomplishments as he is known as the Pioneer of Skiing in America. However, no one knows his name.

A Legacy in the Land

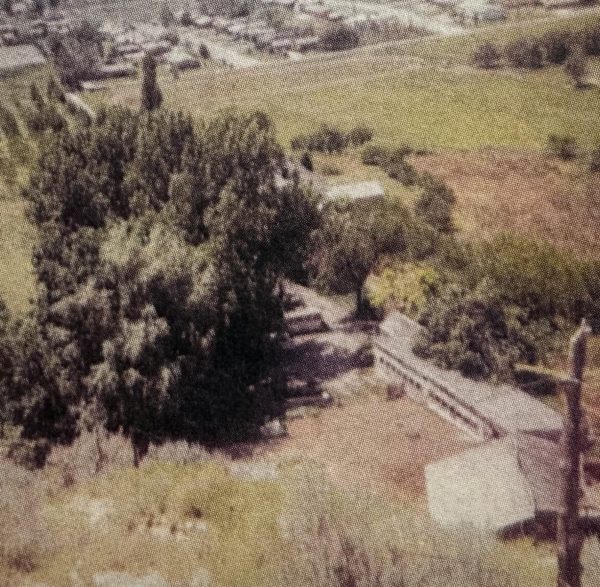

Born in Provo Canyon, Bounous grew up on a farm that stretched from what is now Timpview High all the way past the football field. His family’s property included fruit orchards and vineyards, where he spent much of his childhood, developing a deep connection to the land. During this time, he also began skiing, a passion that would shape his future.

Bounous and his family began building their house in 1964 and finished in 1965. However, once they were finished, change was on the horizon. In 1965, the school board paid the Bounous’s a visit. They said that they owned the land just North of their farm, and they needed their land to make way for development. Junior told them that it was “not for sale” and fought the proposal, hoping to preserve his family’s legacy. He even considered litigation, but he quickly realized that there was no hope as it was Eminent Domain. They took the land away from him, as it was bought up by Provo City, not the school, in 1966. Selling to the city was the only compromise on the situation as Bounous had no choice in the matter.

As bulldozers leveled the area, Bounous lost the fruit trees that had lined the land. The city began converting the land into a park in 1971. That park, which includes the baseball diamond and tennis courts, remained a public space for several years before the high school began construction. Junior even donated the pine trees that still sit there. Then, Provo sold the property to Timpview High School. The soccer field was then quickly built next to the baseball diamond. While the construction plans were running amok, Bounous wanted to be distanced from the school and tried to keep it as North as possible on the land, away from his home. The school began construction and it was opened in 1977. The Bounous family’s property became an integral part of the school’s footprint.

Though reluctant at first, Bounous eventually made peace with the loss, realizing there was little he could do to stop the inevitable. When asked about his thoughts on the presence of the school, Junior said that initially, he “didn’t want [his] land to be taken away.” However, now, he loves the presence of the school, saying that it is “excellent”. Later, it even became a part of his family. He said that he “never had a bad feeling about Timpview”. The school had been with him the whole time.

A New Chapter: From Farm to Skiing

When Bounous graduated in 1943, he pivoted his career to something that would make him a prominent figure in the world of skiing. This pivot started in 1944 when he met Ray Stewart. Stewart owned 4,000 acres of land in Provo Canyon. He sold around 2,000 to Robert Redford to build the resort called Timphaven—now known as Sundance.

Bounous was a mountaineer and financial partner during the development of the Timphaven resort. Junior worked for Redford for 3 years developing the resort, one many of Timpview students are familiar with. Bounous said that it was his “second home.” He would install things like the rope tow and help clear the trees for runs. Bounous contributed significantly to the resort’s early success and ski school.

Later in the 1940s, Junior was working full time in Alta but would work in Timphaven on the weekends. Bounous’s career expanded even further in 1958 when he was offered the position of ski school instructor in California. Taking this job was critical for Junior, as it was the job that really made him. He would work this job in the winters for 6 years, and come back to the Utah resorts in the summer. Working as a director in California put his name into the world and made him who he was.

After this job, Junior continued at Sundance—Timphaven—as an instructor, though he wasn’t on the payroll. Around this time, in 1971, a man named Ted Johnson came along. He was the main developer at the Snowbird resort, and asked for Juniors help to outline the mountain. Bounous debated this offer and ended up deciding to work at Snowbird in the summer and Sundance in the winter. Junior saw the potential that the mountain had, and even outlined all the runs on paper. When the snow melted that year they began cutting the trees and finishing the details of the resort. After the resort was finished, Ted asked Junior if he would like to run the ski school out in Snowbird, he said that he wasn’t applying to be the director but Ted drove a hard bargain.

Junior decided to jump ship from Sundance to Snowbird. Redford was not happy, as Bounous controlled the ski school at Sundance. He took the Sundance ski team, instructors, and staff, which was 80 employees total, to “The Bird”. Bounous stated that he doesn’t blame Redford for this move and he doesn’t know if he would make that move again. Snowbird inherited all of this business successfully, because it was taken directly from Sundance. Since it was a difficult mountain to ski, it was a big challenge, but he grew alongside Snowbird.

Bounous became the Director of skiing at Snowbird, so inevitably, requests for private lessons flew in. Junior was so involved in teaching all the way until he was 89 years old. When he turned 89, he thought to himself that he couldn’t accept paychecks anymore from his clients. He was known for his passion for helping others improve their skiing, and his dedication to his craft earned him a reputation as one of the industry’s most respected figures.

Some skiers at Timpview may be more familiar with Bounous, or more specifically, the run at Sundance named after him, ‘Junior’. When he was still helping develop Sundance, he saw the potential for a run and tried to get it approved by his manager. The manager said no as it was too expensive and too steep. Then, the manager left for a vacation. Junior took his own team and cleared the run. When the manager returned from his vacation, he was furious with Bounous, but then he later named the run “Junior” after him.

When asked about what advice he could give, he gave his philosophy on teaching. He stated that instructors and teachers need to like to work with people, love being in conversations, and want to help people get better. But above all of that, teachers need to like what they’re doing. The love for their professions needs to “come from within.” Specific to skiing, but can be applied to everything, he said that “the desire to instruct has to be greater than a lift ticket.” He finishes this by describing how that will not root success into your life.

Family and Home Life

Bounous’s personal life has been just as remarkable as his professional one. He met his wife, Maxine, while horseback riding, and they married in 1952. Maxine, an excellent ski instructor in her own right, continued teaching well into her 90s. Together, they had children who attended Timpview High, making the school a part of their extended family.

Bounous’s son now lives next door on the original Bounous property, and his grandchildren reside in the basement apartment of his home, which is still there next to Timpview. Though Junior’s land may have been transformed into a school and park, his roots in the community remain as strong as ever.

His Lasting Legacy

Today, Bounous remains a proud member of the Timpview community, although few know the full extent of his contributions. In an interview on October 24, 2024, Bounous expressed his feelings about the high school, his involvement in its creation, and his thoughts on the legacy that bears his name.

When the school had been built, someone had put up a memorial for Bounous that still exists on the South end of the field. “I never asked for the memorial,” Bounous said, referring to the tribute on the soccer field that bears his name. “It was probably the school board’s decision, but I’m happy it’s there. More people should know where this land came from.”

Bounous said that his experience losing his land “is an acceptance of what happens in life, it is not trying to battle with resistance and being thankful for what you have.” For Bounous, the key to happiness lies in appreciating the life you’ve lived and the opportunities you’ve had. “Thankfulness is not limited to money,” he says, “It’s about people, friends, and the environment around you.”

Despite his many accomplishments in skiing, Bounous’s love for the land never faded. He reflected on the importance of appreciating the environment around you, saying, “It’s living within the environment that you’re in and with total enjoyment for the moment and the day. It’s important to accept what you’re doing and where you’re living with full appreciation. If you don’t appreciate or enjoy it, then you have to keep looking. Find what you can do to change it.” For Junior he turned a recreation into a lifetime profession.

In fact, Bounous has spent much of his life surrounded by nature. His connection to the natural world is evident in the way he speaks about it, and his appreciation for the beauty of Utah’s mountains, lakes, and valleys is endless.

Bounous recently went on a tour of the newly constructed highschool with some of the faculty. Everyone that Bounous talked to on this tour said that they didn’t know that he had a memorial. Afterwards, he thought to himself, how many students or teachers know his name is in the field, or know his name at all. Bounous had a hope for this interview, he said that “more people should know about the memorial and my story, and that’s why you’re here, putting into the paper so everyone can see.”

Conclusion

Junior Bounous’s contributions to Timpview High School and the world of skiing are often overshadowed by the passage of time. Yet, his legacy endures, both in the memories of those who worked with him and in the land that he helped shape. As Bounous enters his 100th year, he remains a hero. At the end of the interview, Bounous summed it up simply: “It’s about living with no regrets, enjoying every day, and being thankful for the environment you’re in.” For Junior Bounous, that environment has included Timpview High, the ski slopes, and the mountains he loves—a testament to a life well-lived.

Note

On October 24, Staff Writer Millie Mason and I had the chance to interview Mr. Bounous. This was my first experience as a true journalist and it was so meaningful to me. Millie and I spent over an hour talking to Bounous in his home living room. His plaques and achievements lined the walls, such as pictures of him skiing, photos of him carrying the 2002 Olympic torch (and the torch itself was the centerpiece), memorabilia of his wife, old skis, his family, and so much more. Seeing his life laid out in his living room was really powerful. This was a man with a story to tell and I needed to share it. Bounous greeted Millie and I outside, using a skiing poles and walking sticks. He had a bandage on his arm as he had just gotten back from a camping trip (he acted like he was 25 years old). This was a man who had jumped out of a helicopter on skis just 4 years ago (at 95 years old!), setting a world record. I think that we as a community have a lot to learn about Junior’s story. I hope my fellow peers can use his story of motivation and resilience to empower our own lives.

His granddaughter wrote a book about his life, it is titled Junior Bounous and the Joys of Skiing, and he gifted it to me. I encourage you to read this book in order to learn more about your community or just because he is an amazing person.

Ken Nelson • Apr 26, 2025 at 11:36 AM

I met this wonderful man while skiing at Alta this April. I had started to thinking of myself as an “old man”. I enjoy meeting people while riding the lifts. I told Mr. Bounous that I usually had seniority when rinding the lifts. His son informed me that his dad was 99 years old. He is an absolutely charming person, full of life and a contiguous positive attitude. I felt like he was younger than me.

Marklee Reveal • Apr 5, 2025 at 3:34 PM

How fantastic!!!! Great work. Timpview graduate 1979.

Elizabeth • Nov 20, 2024 at 7:52 PM

This article is truly incredible. Thank you for sharing his awesome story!

Miles Welch • Nov 19, 2024 at 10:57 PM

this is an incredible article that’s really well done, more people need to know about this story